Have you ever wanted to own a piece of the biggest companies in America, like Apple, Amazon, or Costco, but felt you didn’t have enough money to buy them all individually? You are not alone. Many new investors face this exact hurdle when they start their financial journey.

This is where understanding how mutual funds work becomes a game-changer. Think of a mutual fund like a giant carpool. Instead of everyone driving their own car and navigating the complex traffic of the stock market alone, a group of investors chips in to hire a professional driver.

That driver is a fund manager, and the car is the mutual fund. By pooling your money with thousands of other people, you can go places—and buy assets—that would be impossible to reach on your own. In this guide, we will break down everything you need to know about this essential investment tool.

What Exactly Is a Mutual Fund?

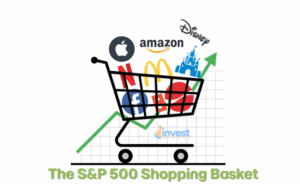

At its simplest level, a mutual fund is a company that brings together money from many people and invests it in a variety of stocks, bonds, or other assets. When you buy a share of a mutual fund, you aren’t buying a single stock. Instead, you are buying a tiny piece of a massive “basket” of investments.

If the basket contains 100 different companies, and you own one share of the fund, you technically own a small slice of all 100 of those businesses. This structure is what makes how mutual funds work so attractive to beginners: it provides instant variety with very little effort.

The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) regulates these funds to ensure they follow specific rules about what they can buy and how they report their progress to you. This oversight provides a layer of security, knowing that the fund must be transparent about where your money is going.

How Mutual Funds Work: The Power of the Pool

To understand the mechanics, imagine you and 500 neighbors want to start a community garden. None of you has enough money to buy a massive plot of land, expensive tractors, or exotic seeds on your own. However, if everyone puts in 100 dollars, the group suddenly has 50,000 dollars.

With that 50,000 dollars, the group can buy the best land and hire a master gardener to do the hard work. In the investing world, that 100 dollars is your “investment,” the 50,000 dollars is the “mutual fund,” and the master gardener is the “fund manager.”

The 4-Step Breakdown of Pooling Money:

- Plain English: You combine your small amount of money with the small amounts of thousands of others to create a huge pile of cash that can buy “bulk” investments.

- Real Example: Imagine you want to invest in TSLA (Tesla), JPM (JPMorgan Chase), and WMT (Walmart). Individually, buying one share of each could cost hundreds or even thousands of dollars. By putting 50 dollars into a “Total Stock Market” mutual fund, you might own a tiny fraction of all three, plus 500 other companies.

- Common Mistake: Newbies often think they “directly” own the stocks inside the fund. They might try to call the fund and ask to sell just their “portion” of Apple stock.

- Correct Mindset: You own shares in the fund itself, not the individual stocks. The fund owns the stocks; you own a piece of the fund’s total value.

Diversification: Why You Don’t Put All Your Eggs in One Basket

The biggest advantage of knowing how mutual funds work is a concept called diversification. This is a fancy way of saying “don’t risk everything on one company.” If you put all your savings into a single tech company and that company has a bad year, your entire savings could vanish.

In a mutual fund, if one company in the basket fails, the other 99 might still be doing great. The success of the many helps protect you from the failure of the few. It is the ultimate safety net for someone who doesn’t have the time to research every single company on the stock market.

The 4-Step Breakdown of Diversification:

- Plain English: Diversification is like having a balanced diet. You don’t just eat spinach; you eat fruits, grains, and proteins so that if the spinach crop fails, you don’t starve.

- Real Example: Consider a “Sector Fund” that focuses on technology. It holds AAPL, MSFT, and NVDA. If a specific regulation hurts one company, the others in the fund help stabilize your total balance.

- Common Mistake: Beginners sometimes think that owning five different mutual funds means they are “extra diversified.” However, if all five funds own the same 50 stocks, you aren’t actually diversified—you are just paying five different managers to buy the same thing.

- Correct Mindset: True diversification means owning different types of assets, like a mix of stocks and bonds, or a mix of US and international companies.

Professional Management: Hiring a Pro to Do the Heavy Lifting

One of the main reasons people ask about how mutual funds work is because they don’t want to spend eight hours a day reading financial reports. When you invest in a mutual fund, you are hiring a professional manager—usually someone with an advanced degree and a team of researchers.

These managers spend their entire day looking at charts, talking to CEOs, and analyzing the economy. They decide when it is the right time to buy more shares of a company like AMZN (Amazon) or when it is time to sell some shares of a retail giant like TGT (Target).

The 4-Step Breakdown of Professional Management:

- Plain English: You are paying a small fee to let an expert make the “Buy” and “Sell” decisions for you.

- Real Example: A fund manager at a large firm like Fidelity or Vanguard monitors the market daily. If they see a sector like renewable energy growing, they might move more of the fund’s money there without you having to lift a finger.

- Common Mistake: Many beginners assume that because a manager is a “pro,” they will always make money. They expect the manager to have a “crystal ball.”

- Correct Mindset: Managers are human and the market is unpredictable. Even the best pros can have “down” years. You are paying for their process and expertise, not a guarantee of profit.

The Cost of the Ride: Understanding Expense Ratios

Nothing in life is free, and the same goes for mutual funds. Since you are hiring a manager and a team of researchers, you have to pay them. This cost is called the Expense Ratio. It is a small percentage of your investment that the fund takes every year to cover its bills.

For example, if a fund has an expense ratio of 1%, and you have 1,000 dollars in the fund, the company will take 10 dollars over the course of the year to pay for their services. This happens automatically, so you usually don’t even see a bill.

The 4-Step Breakdown of Expense Ratios:

- Plain English: The expense ratio is like the “membership fee” for the fund. The lower the fee, the more money stays in your pocket to grow over time.

- Real Example: If you invest 10,000 dollars in a fund with a 0.5% fee, you pay 50 dollars a year. If the fee is 1.5%, you pay 150 dollars. Over 30 years, that 100-dollar difference can grow into thousands of dollars of lost potential wealth.

- Common Mistake: Beginners often ignore the expense ratio because “1%” sounds like a tiny number. They focus only on the “Returns” column.

- Correct Mindset: Fees are one of the only things in investing that you can actually control. Choosing a low-cost fund is often more important than trying to find the “hottest” manager.

NAV: How is the Price Calculated?

When you buy a regular stock, the price changes every second. You can watch it go up and down on your phone like a heart monitor. Mutual funds are different. They only update their price once a day, usually after the stock market closes at 4:00 PM Eastern Time.

This price is called the Net Asset Value (NAV). To figure this out, the fund company adds up the value of everything the fund owns, subtracts any debts or fees, and divides that total by the number of shares people own.

The 4-Step Breakdown of NAV:

- Plain English: The NAV is the “fair price” of one share of the fund at the very end of the day. It’s like checking the total value of your community garden only after the sun goes down and all the crops have been counted.

- Real Example: If a fund owns assets worth 1 million dollars and there are 100,000 shares held by investors, the NAV would be 10 dollars per share. If you invest 100 dollars, you get 10 shares.

- Common Mistake: People often try to “day trade” mutual funds, buying in the morning and selling in the afternoon.

- Correct Mindset: You cannot day trade mutual funds because you won’t know the exact price you bought or sold at until the end of the day. They are designed for long-term holding, not quick flipping.

Active vs. Passive Funds: Which Path is Yours?

As you explore how mutual funds work, you will run into two main “flavors”: Active and Passive.

- Active Funds: The manager is trying to “beat” the market. They are actively picking winners and losers. These usually have higher fees because more work is involved.

- Passive Funds (Index Funds): The manager isn’t trying to outsmart anyone. They just buy everything in a specific list, like the S&P 500. If the list includes COST (Costco), they buy Costco. These are much cheaper because they don’t need a huge team of researchers.

The 4-Step Breakdown of Active vs. Passive:

- Plain English: Active is like hiring a chef to cook a custom meal; Passive is like a self-service buffet where the food is already laid out according to a set menu.

- Real Example: An active fund might try to predict that tech stocks will fall and energy will rise. An index fund (passive) will just own both and follow the general flow of the market.

- Common Mistake: Beginners often think “Active” must be better because someone is “trying harder.”

- Correct Mindset: Statistically, many passive funds actually perform better than active ones over the long term because their fees are so much lower.

Mutual Funds in Your Retirement Account

If you work for a company in the US, you probably have a 401(k) or a 403(b). If you have opened one yourself, it’s likely an IRA (Individual Retirement Account). These accounts are almost entirely built on mutual funds.

The IRS and SEC have designed these retirement vehicles to encourage long-term, diversified investing. Mutual funds are the “building blocks” of these accounts because they allow a 22-year-old starting their first job to own a diverse portfolio with just 50 dollars from their first paycheck.

Current regulations often allow for “automatic rebalancing” within these funds. This means if your stocks grow too fast and your bonds fall behind, the fund automatically adjusts itself to stay at your desired risk level.

Common Pitfalls for New Mutual Fund Investors

Even though mutual funds are designed for beginners, there are still ways to stumble. Understanding how mutual funds work also means understanding the psychological traps.

- Chasing Yesterday’s Winner: Many people look for the fund that grew the most last year and put all their money there. But last year’s winner is often next year’s loser. Markets move in cycles.

- Panic Selling: When the market dips, the value of your mutual fund shares will drop. This is normal. The mistake is selling when the price is low. Remember, you still own the same number of shares; they are just “on sale” at the moment.

- Ignoring Taxes: Unless your fund is in a tax-advantaged account like an IRA, you might have to pay taxes when the manager sells stocks inside the fund, even if you didn’t sell your fund shares. This is called a capital gains distribution.

How to Get Started

If you are ready to put this knowledge to work, the process is simpler than it used to be. Most major brokerage firms in the US allow you to open an account online in minutes.

- Open an Account: Choose a reputable provider (like Vanguard, Fidelity, or Charles Schwab).

- Check the Minimums: Some funds require 1,000 dollars to start, while others have a zero-dollar minimum if you set up a monthly contribution.

- Look for “No-Load” Funds: A “load” is just a fancy word for a sales commission. You should almost never pay a “front-end load” to buy a fund. Stick to “no-load” funds to keep your costs down.

- Automate It: The best way to benefit from how mutual funds work is to set up a “Systematic Investment Plan.” This means you contribute a set amount—say 100 dollars—every single month regardless of whether the market is up or down.

Regulations regarding tax limits for retirement accounts and fund disclosure requirements can change. It is always a good idea to check the current IRS guidelines or consult with a qualified financial professional to see how these investments fit into your specific tax situation.

Final Thoughts: The Long-Distance Journey

Mutual funds aren’t a “get rich quick” scheme. They are a “get wealthy slowly” tool. By sharing the ride with professional managers and thousands of other investors, you gain access to the growth of the global economy without needing to be a math genius or a Wall Street insider.

The most important step isn’t picking the “perfect” fund—it’s starting. Every month you wait is a month of missed growth. Now that you know the basics of how mutual funds work, you have the map. It’s time to start the engine.

Disclaimer: This content is for educational purposes only and does not constitute financial, legal, or tax advice. Investing involves risk, including the possible loss of principal. Past performance does not guarantee future results.