Have you ever looked at your bank account at the end of the month and wondered where all your money went? You worked hard, you got paid, yet the balance seems to have vanished into thin air. If this sounds familiar, you are not alone. Many people in the United States live in a state of “financial mystery,” where money flows in and out without a clear plan.

Mastering zero-based budgeting is the ultimate solution to this mystery. This isn’t just a way to track what you spent; it is a way to tell your money exactly what to do before the month even begins. In this guide, we will break down how to give every single dollar a specific job so you can finally take control of your financial future.

What is Zero-Based Budgeting?

At its heart, zero-based budgeting is a method of income management where your total income minus your total expenses equals exactly zero. This does not mean you have zero dollars in your bank account. Instead, it means that every cent you earn has been assigned to a specific category—whether that is for rent, groceries, a high-yield savings account, or even a retirement fund.

Imagine you earn 4,000 dollars in a month. With this method, you don’t just spend and hope for the best. You sit down and decide that 1,500 dollars goes to rent, 400 dollars to groceries, 500 dollars to your Roth IRA, and so on, until all 4,000 dollars are accounted for. By the time you are done planning, there is not a single dollar left “unemployed.”

Why Beginners Often Get It Wrong

Many beginners think that “zero-based” means they are supposed to be broke. They see the “zero” and feel a sense of panic, thinking they aren’t allowed to have a cushion or an emergency fund. They assume this method is only for people who are struggling to make ends meet.

The Mindset Shift

The reality is that zero-based budgeting is about intentionality, not deprivation. Having a “zero” balance at the end of your planning phase means you are the boss of your money. It ensures that your savings and investments are treated as “expenses” that you pay to yourself. This shift from “spending what is left” to “assigning everything first” is what builds real wealth.

Step 1: Identify Your Total Take-Home Income

The first step to mastering this budget is knowing exactly how much money is hitting your bank account. In the U.S., this is your “net pay” or “take-home pay”—the amount left after your employer takes out federal taxes, Social Security, and health insurance premiums.

For example, if you work at a major company like Walmart or Amazon, your pay stub will show your gross pay and then a list of deductions. For our budget, we only care about the final number that gets deposited into your checking account. If you have a side hustle, like driving for Uber or selling items on Etsy, you must include that estimated income as well.

A Common Calculation Error

A frequent mistake for newcomers is budgeting based on their gross salary (the big number on the job offer) rather than their actual take-home pay. If you earn 60,000 dollars a year, you might think you have 5,000 dollars a month to spend. But after taxes and benefits, you might only see 3,800 dollars.

Adjusting Your Logic

Always budget with the money you actually have. If you budget using your gross income, you will overspend every single month because the government takes its share before you even see it. Look at your last two or three pay stubs to find your true monthly average.

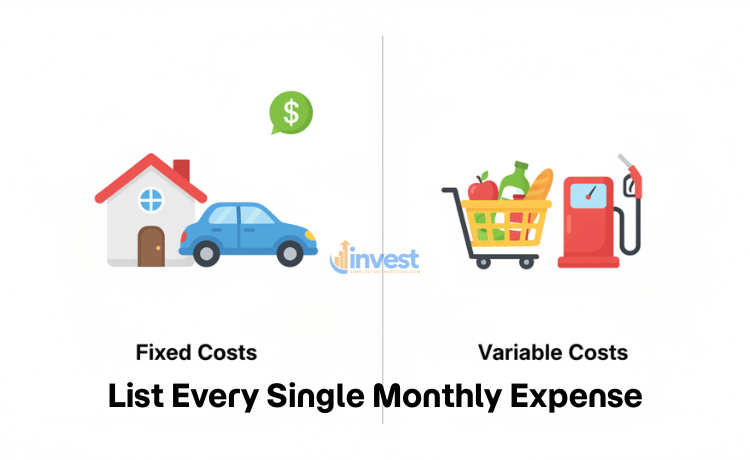

Step 2: List Every Single Monthly Expense

Now comes the part where you look at where the money goes. You need to list every single thing you spend money on. To make this easier, we divide these into two groups: fixed expenses and variable expenses.

Fixed expenses stay the same every month. Think of your rent or mortgage, your car payment, or your Netflix subscription. Variable expenses change based on your behavior, such as groceries, dining out, or gas for your car. Many Americans are finding that utility bills and groceries are more expensive due to inflation, so it is important to use recent numbers, not what you paid two years ago.

The “Hidden Expense” Trap

New budgeters often forget about “non-monthly” expenses. These are things like your annual car registration, a semi-annual car insurance bill, or holiday spending. Because these don’t happen every month, they are often left out of the budget entirely, leading to a financial crisis when the bill finally arrives.

The Sinking Fund Strategy

To fix this, use what we call a sinking fund. If your car insurance is 600 dollars every six months, treat it as a 100-dollar monthly expense. By “giving a job” to those 100 dollars every month, the money will be sitting there waiting for you when the bill comes due. This turns a “financial emergency” into a non-event.

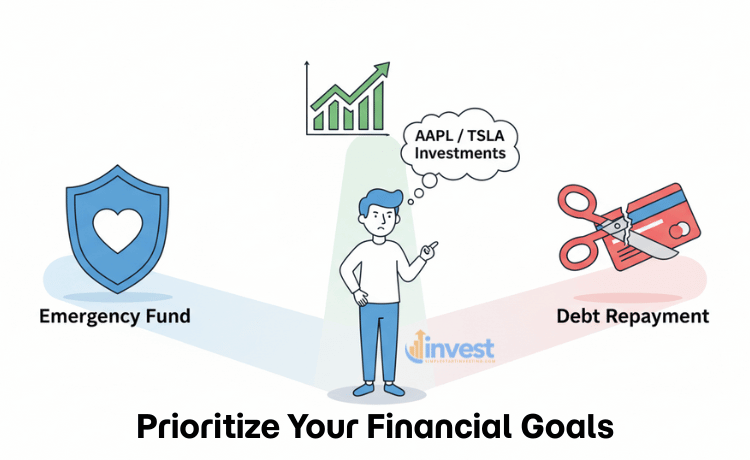

Step 3: Prioritize Your Financial Goals

This is where zero-based budgeting becomes powerful. Before you spend money on “wants” like new clothes or a trip to Starbucks, you must assign money to your future. This includes building an emergency fund, paying off high-interest debt (like credit cards), and investing in the stock market.

For instance, you might decide to buy shares of an index fund or a popular company like Apple (AAPL) through your brokerage account. In a zero-based budget, that 200-dollar investment is just as important as your electric bill. You assign it a job right at the beginning.

The “Leftover” Misconception

Most people wait until the end of the month to see if there is any money left to save. The problem is that there is almost never money left. Life has a way of “eating” unassigned dollars. You see a sale at Target, or you decide to order delivery, and suddenly your savings goal for the month is gone.

Pay Yourself First

In the zero-based system, you “pay yourself first.” You treat your savings and investments as mandatory bills. If you want to save 500 dollars a month, that 500 dollars gets its “job” assigned before you ever look at your entertainment budget. This ensures you are building wealth consistently.

Step 4: Do the Math to Reach Zero

Once you have listed your income and all your categories (bills, food, savings, fun), you subtract the expenses from the income. Your goal is to reach exactly zero.

If you have 4,000 dollars in income and your listed expenses add up to 3,700 dollars, you are not done. You have 300 dollars “unemployed.” You must give those 300 dollars a job. You could put them toward your student loans, add them to your vacation fund, or increase your investment in Tesla (TSLA).

What If You Have a Negative Number?

If your expenses total 4,200 dollars but you only earn 4,000 dollars, you have a problem. You are overspending. Beginners often ignore this and just let the balance go onto a credit card, which creates a cycle of debt.

Balancing the Scale

If you are in the negative, you must make cuts. Look at your variable expenses first. Can you reduce your dining out budget? Can you cancel a subscription you don’t use? The goal is to keep adjusting the numbers until your income minus your expenses equals zero. This process forces you to make hard choices now so that you don’t have to face a crisis later.

Handling Variable Income

In today’s economy, many people don’t have a steady paycheck. Maybe you are a freelancer or work in the “gig economy.” You can still use zero-based budgeting. The trick is to budget based on your lowest expected monthly income.

If you usually earn between 3,000 and 5,000 dollars, create your baseline budget using 3,000 dollars. This ensures your “must-have” bills (rent, food, utilities) are always covered. If you end up earning 4,500 dollars that month, you simply sit down and “give a job” to the extra 1,500 dollars as soon as it arrives.

The “Windfall” Mistake

When people with variable income have a “good month,” they often treat the extra money as a “free pass” to splurge. They spend it without a plan, forgetting that a “bad month” might be just around the corner.

Creating a Buffer

Use your high-income months to build a “buffer” or a “hill and valley” fund. This is a specific category in your budget where you park extra cash to help cover your bills during low-income months. This keeps your financial life stable regardless of how much you earn in a specific week.

Using Technology to Track Your Progress

While you can do this with a pen and paper, many Americans find success using apps like YNAB (You Need A Budget) or Rocket Money. These tools connect to your bank account and help you see in real-time if you are staying within the “jobs” you assigned to your dollars.

For example, if you assigned 400 dollars to groceries but you spent 100 dollars at Costco and another 350 dollars at Whole Foods, the app will show that you are 50 dollars over budget. You must then “borrow” those 50 dollars from another category, like your “dining out” fund, to bring the grocery category back to balance.

The “Set It and Forget It” Fallacy

A major mistake is creating a budget on the first of the month and then never looking at it again. A budget is a living document. Life happens—you might get a flat tire or an unexpected invite to a wedding.

Active Management

Check your budget at least once a week. If you overspent in one area, adjust another area immediately. This active management is what prevents the “end-of-the-month surprise” where you realize you’ve overdrawn your account.

The Long-Term Benefits of Every Dollar Having a Job

Mastering zero-based budgeting is the fastest way to reach “Financial Freedom.” When you account for every cent, you stop wasting money on things that don’t matter to you. You start seeing your bank account as a tool for building the life you want.

Within a few months of using this method, most people find “extra” money they didn’t know they had. That money can be used to fund a house down payment, start a business, or invest for retirement. By being intentional, you turn your income into a powerful engine for wealth.

Summary Checklist for Beginners

- Calculate your true take-home pay after all taxes and deductions.

- List every fixed bill, from rent to your gym membership.

- Estimate variable costs like food and gas, using recent high-inflation prices.

- Assign money to your goals first (savings, debt, and investments).

- Subtract expenses from income until the result is exactly zero.

- Track your spending weekly and adjust your categories as needed.

Disclaimer: This content is for educational purposes only and does not constitute financial advice.