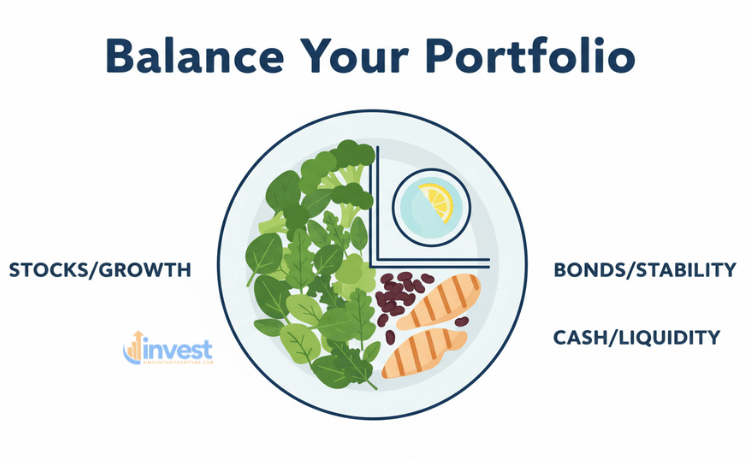

Imagine you are standing in front of a giant buffet. You see a vibrant salad bar, a section with hearty steaks, and a table filled with delicate desserts. If you only eat the desserts, you might feel great for ten minutes, but you’ll probably have a stomachache later. If you only eat the lettuce, you’ll stay lean, but you might run out of energy before the day is over. Successful investing is a lot like filling that plate. You need a mix of different foods to stay healthy, energized, and satisfied. In the financial world, this “plate-filling” strategy is known as Asset Allocation for Beginners.

At its core, asset allocation is simply the process of deciding how to divide your money among different types of investments. Instead of putting all your eggs in one basket, you spread them out. This isn’t just about being organized; it is the most important decision you will ever make as an investor. Research has shown that the way you split your money between broad categories like stocks and bonds matters far more than which specific company’s stock you choose to buy. If you want to build wealth without losing sleep every time the news mentions a market dip, understanding your mix is the first step.

What is Asset Allocation?

To understand asset allocation, we first need to look at what an “asset” actually is. In the world of finance, an asset is just a “bucket” where you can put your money with the hope that it will grow or provide safety. The three main buckets most people use are stocks, bonds, and cash. Asset Allocation for Beginners focuses on how much of your total “pie” goes into each of these three buckets.

Step 1: Plain English Explanation Think of asset allocation as the recipe for your financial future. If you are baking a cake, the ratio of flour to sugar to eggs determines whether the cake is light and fluffy or dense and sweet. In your portfolio, the ratio of stocks to bonds determines how fast your money might grow and how much it might “shake” when the economy gets bumpy. It is the master plan that keeps you on track toward your goals, like buying a home or retiring comfortably.

Step 2: Real-World US Example Let’s say you have 10,000 dollars to invest. You decide on a “60-40 split.” This means you put 6,000 dollars into stocks (like buying shares of a broad fund that owns companies like Walmart or Costco) and 4,000 dollars into bonds (which are essentially loans you make to the government or big companies). If the stock market has a rough year, that 6,000 dollars might drop in value. However, the 4,000 dollars in bonds usually stays more stable, acting as a cushion so your total 10,000 dollars doesn’t disappear overnight.

Step 3: Common Beginner Mistake Many new investors think they should just pick the “best” stock they hear about on the news. They might put all their money into a single high-flying tech company because they saw a headline about a new invention. They believe that “investing” means finding the one winner that will make them rich.

Step 4: The Correct Mindset The truth is that even the best companies can have bad years. By focusing on asset allocation instead of individual “picks,” you are acknowledging that you cannot predict the future. You aren’t trying to find the one needle in the haystack; you are buying the whole haystack and then adding a protective layer of blankets (bonds) over it. This shift in focus from “picking winners” to “managing the mix” is what separates professional investors from gamblers.

Stocks: The Growth Engine of Your Portfolio

When we talk about stocks, we are talking about owning a piece of a company. If you own a share of Amazon, you technically own a tiny slice of their warehouses, their website, and their future profits. Stocks are generally the “riskiest” part of a beginner’s portfolio, but they also offer the highest potential for growth over the long term.

Step 1: Plain English Explanation Stocks are like the engine in a car. They provide the power and speed needed to get you to your destination (wealth) quickly. Without stocks, your money might not grow fast enough to beat the rising cost of living, also known as inflation. However, like a powerful engine, they can be loud, hot, and sometimes a bit scary when they rev too high.

Step 2: Real-World US Example Consider a company like Apple (AAPL). If you bought shares of Apple years ago, your money would have grown significantly because the company sold millions of iPhones and services. But there have been times when Apple’s stock price dropped by 20 percent or more in a single year due to global trade issues or supply chain problems. If Apple was your only investment, you’d be feeling a lot of pain. But in a diversified asset allocation, Apple is just one of many “growth engines” working for you.

Step 3: Common Beginner Mistake New investors often flee the stock market the moment prices start to drop. They see their account balance go from 5,000 dollars to 4,500 dollars and panic, thinking it will go to zero. They treat the stock market like a building on fire and run for the exit at the worst possible time.

Step 4: The Correct Mindset The correct way to view stocks is as a long-term partnership. Markets go up and down, but over decades, the US economy has historically grown. You should expect your stock “bucket” to be volatile. That volatility is the “fee” you pay for the chance to earn higher returns. If you have 20 years before you need the money, a temporary dip in stock prices is actually an opportunity to buy more “engines” at a discount.

Bonds: The Shock Absorber for Your Money

If stocks are the engine, bonds are the shock absorbers. A bond is basically a “I owe you” note. When you buy a bond, you are lending money to an organization (like the US Government) for a set period. In return, they promise to pay you back your original money plus a little bit of interest along the way.

Step 1: Plain English Explanation Bonds provide stability. While they usually don’t grow as fast as stocks, they are much less likely to lose value suddenly. When the stock market is “bumpy,” bonds help keep the ride smooth. They pay you regular interest, which acts like a small, steady paycheck for your portfolio.

Step 2: Real-World US Example Imagine you buy a US Treasury Bond. Currently, these are considered some of the safest investments in the world because they are backed by the “full faith and credit” of the US government. If the stock market crashes because of a global crisis, investors often rush to buy Treasury bonds for safety. This means while your stocks are losing value, your bonds might actually hold steady or even increase in value, protecting your total account.

Step 3: Common Beginner Mistake Many beginners think bonds are “boring” or “useless” because they don’t see the massive gains they see in stocks. They might say, “Why should I earn 4 percent in a bond when I can earn 15 percent in a tech stock?” They often decide to skip bonds entirely to “maximize” their gains.

Step 4: The Correct Mindset Bonds aren’t there to make you rich; they are there to keep you from becoming poor. Their job is to prevent you from panicking. If your entire portfolio is in stocks and it drops by 40 percent, you might be tempted to sell everything and quit. If you have a healthy dose of bonds, that same market crash might only drop your total value by 20 percent. That difference is often what allows an investor to stay calm and stay invested.

Cash and Cash Equivalents: The Emergency Brake

Cash isn’t just the physical bills in your wallet. In your investment account, “cash” usually refers to very safe, very accessible places to store money, like a High-Yield Savings Account (HYSA) or a Money Market Fund.

Step 1: Plain English Explanation Cash is your “liquidity.” It is the money you can grab immediately if you have an emergency or if you see a great opportunity to buy something else. It doesn’t really grow—in fact, after inflation, it might actually lose a tiny bit of “buying power”—but it is the only asset that is guaranteed to be there when you need it.

Step 2: Real-World US Example Think of a major US retailer like Target. They keep cash on hand to pay their employees and buy inventory. Similarly, an investor might keep 5 percent of their portfolio in a Money Market Fund. If you lose your job or your car breaks down, you can pull that money out without having to sell your stocks while they might be “down” in value.

Step 3: Common Beginner Mistake Beginners often fall into two extremes: they either keep way too much cash (because they are afraid of the market) or they keep zero cash (because they want every penny to be “working”). Keeping too much cash means your money loses value to the rising cost of groceries and gas. Keeping too little means you might be forced to sell your investments at a loss during a personal emergency.

Step 4: The Correct Mindset Cash is like an insurance policy. You don’t expect it to make you a profit; you pay for the peace of mind it provides. A small slice of your asset allocation should almost always be “liquid” so that life’s surprises don’t derail your long-term investment plan.

How to Pick Your Perfect Mix

Now that you know the ingredients, how do you decide how much of each to put on your plate? This depends on two things: your Time Horizon and your Risk Tolerance.

Your Time Horizon (The “When”)

This is simply how long you have until you need the money. If you are 25 years old and saving for a retirement that is 40 years away, you can afford to have a lot of stocks. If the market crashes tomorrow, you have four decades for it to recover. However, if you are 60 and planning to retire in three years, you need to be much more careful. You don’t have time to wait for a 10-year recovery.

Your Risk Tolerance (The “Feel”)

This is about your personality. How would you feel if you opened your laptop and saw that your 10,000 dollars had turned into 7,000 dollars? If that thought makes you feel sick or want to cry, you have a low risk tolerance. You need more bonds. If you can look at that drop and say, “Well, the market is on sale, I should buy more,” you have a high risk tolerance.

The “Age-Based” Starting Point

A classic rule of thumb for Asset Allocation for Beginners used to be the “100 minus your age” rule. You would take the number 100, subtract your current age, and the result was the percentage of your money that should be in stocks.

For example, if you are 30 years old:

- Take 100 and subtract 30.

- The result is 70.

- So, you would put 70 percent of your money in stocks and 30 percent in bonds.

Modern Adjustments: Because people are living longer today, many experts now use 110 or even 120 as the starting number. If you use 120 and you are 30 years old, you would put 90 percent in stocks and 10 percent in bonds. This allows for more growth over a longer life.

Common Mistake: Many beginners follow these rules blindly without checking their own feelings. They might be 25 years old and put 95 percent of their money in stocks because a “rule” told them to. Then, the market drops 10 percent, and they panic-sell everything because they weren’t emotionally ready for that much “shake.”

Correct Mindset: Use these age-based rules as a “suggestion,” not a law. The best asset allocation is the one you can actually stick with when things get scary. It is better to have a “slower” portfolio with more bonds that you never sell, than a “fast” portfolio that you dump the moment it hits a pothole.

The Power of Rebalancing

Once you pick your mix—say, 70 percent stocks and 30 percent bonds—you can’t just walk away forever. Over time, the stock market usually grows faster than the bond market. After a few years, your 70 percent stocks might have grown so much that they now make up 80 percent of your portfolio.

Step 1: Plain English Explanation Rebalancing is the act of “resetting” your portfolio back to your original plan. If your stocks have grown too big, you sell a little bit of them and use that money to buy more bonds. This brings you back to your 70-30 split.

Step 2: Real-World US Example Imagine you own shares in Tesla (TSLA) and some US government bonds. Tesla has a massive year and the stock price doubles. Now, Tesla makes up a huge portion of your account. You are now much “riskier” than you planned to be. To rebalance, you would sell some of those high-priced Tesla shares and buy more bonds.

Step 3: Common Beginner Mistake The biggest mistake beginners make is falling in love with their winners. They say, “My stocks are doing great! Why would I sell the thing that is making me money just to buy ‘boring’ bonds?” They let their winners run until they are completely over-exposed. Then, when the market eventually turns around, they lose much more than they should have.

Step 4: The Correct Mindset Rebalancing is a “cheat code” for investing. It forces you to do the two hardest things in finance: Buy Low and Sell High. When you sell your “grown” stocks to buy bonds, you are selling at a high price. If the market crashes and your stocks become a smaller part of your portfolio, you sell bonds to buy more stocks, which means you are buying stocks while they are “on sale” (low price). You don’t need to be a genius to time the market; you just need to rebalance once a year.

2026 Context: Taxes and Limits

As you build your asset allocation, it’s important to know where you are putting that money. In the US, we have special “buckets” with tax benefits.

For this year, the IRS has updated the limits for how much you can contribute to these accounts. If you are using a 401(k) through your employer, you can contribute up to 24,500 dollars. If you are using an IRA (Individual Retirement Account), the limit is 7,500 dollars. If you are age 50 or older, you can add even more as a “catch-up” contribution—an extra 8,000 dollars for your 401(k) and 1,100 dollars for your IRA.

Why does this matter for asset allocation? Because different assets are taxed differently. Some investors prefer to keep their “fast-growing” stocks in tax-free accounts (like a Roth IRA) and their “interest-paying” bonds in tax-deferred accounts (like a traditional 401k). However, for a total beginner, the most important thing is simply getting the mix right across all your accounts combined.

Note: Tax laws and contribution limits can change every year. Always check the current IRS guidelines or talk to a tax professional when planning your contributions.

Final Thoughts for Your Journey

Asset Allocation for Beginners isn’t about finding a magic formula. It’s about balance. It’s about making sure that your “growth engine” is powerful enough to get you to your goals, but your “shock absorbers” are strong enough to keep you from jumping out of the car when the road gets rough.

Start by asking yourself:

- When do I need this money? (5 years? 20 years?)

- How much “shaking” can I stand?

- What is my simple percentage split?

Once you have that split—whether it’s 60-40, 80-20, or something else—write it down. Stick to it. Rebalance it once a year. If you can do those three simple things, you will already be ahead of the vast majority of people trying to “play” the stock market. You aren’t playing a game; you are building a future.

Disclaimer: This content is for educational purposes only and does not constitute financial advice. Investing involves risk, including the potential loss of principal. Please consult with a qualified financial or tax professional before making any investment decisions.